The Little Ice Age, The New Hot Age

The need to adapt, with lessons from the 17th century

I am half-way through one of the most eye-opening books I’ve ever read. It is Geoffrey Parker’s ‘Global Crisis: War, Climate Change & Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century’. Mr Parker is a history professor at Ohio University, and ‘Global Crisis’ was published by Yale University Press in 2013. It’s a brilliant monster, which the publisher hoped could be tamed via a (more expensive) abridged version.

Parker’s book is absolutely huge, stuffed as a budget airline overhead locker with data, histories, anecdotes. I probably should not try to summarize, but here we go:

On the rare occasions we the 17th century’s Little Ice Age crosses our British minds, it tends to conjure up images of merry fairs on the frozen River Thames.

In fact, the Little Ice Age was a genuine global catastrophe. Parker writes: ‘In the mid-seventeenth century, the earth experienced some of the coldest weather recorded in over a millennium. Perhaps one-third of the human population died.’ It hit all of Euro-Asia, it hit the Indian subcontinent, it hit Africa. Britain got off exceptionally lightly, with population falling by only around 8%. Perhaps that’s why we’ve forgotten it.

There is no consensus about 17th century temperatures: Parker usually thinks global temperatures fell by 1-2 degrees C in the mid-17th century but on occasion he goes so far as 3 degrees. Still, he cites mountains of evidence to reach these tentative estimates. Wikipedia, on the other hand, urges us to discount the whole idea of the Little Ice Age.

The effects of rapid temperature change turned out to be non-linear, both industrially and socially/politically. Take its impact on rice production: ‘Even without frosts, a fall of 2 degrees C during the growing season - precisely the scale of global cooling in the 1640s - reduces rice harvest yields by between 30 and 50 percent, and also lowers the altitude suitable for wet-rice cultivation by about 1,300 feet.

“Likewise, in cereal-growing regions, a fall of 2 degrees C shortens the growing season by three weeks or more, diminishes crop yield by up to 15% and lower the maximum altitude at which crops will ripen by about 300 feet.”

But when marginal farming drops out of the supply chain completely, food becomes scarce just at the time when demand for it rises, (because all of those marginal farmers also used to feed themselves).

This is only one of a number of negative feedback loops.

Some feedbacks kicked in to affect the climate directly (probably): the drop in temperatures redistributed air pressure patterns which in turn led to an unprecedented run of El Ninos. El Nino transfers a massive weight of water to and from the East and West coast of the Pacific. The extra pressures on the Ring of Fire tectonic plates plausibly contributed to the sharp rise in volcanic activity seen in the 17th century. That volcanic activity blasted enough ash in the air to cut temperatures even further.

And there were negative political feedbacks. Scapegoats were sought - this was a great time if you were a witch burner, and (of course) a very bad time if you were Jewish. The hunt for scapegoats didn’t calm things down, and discontent eventually degenerated into incessant warfare almost everywhere. After all, a world which is over-populated loses respect for the value of individual human life. (‘Solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short’ - Leviathan 1651). When the world is unable to feed itself, leader must fall, and raiding, warfare, colonisation, slavery, can all suddenly seem like pretty good ideas.

In due course, unending warfare destroys government finances globally, which in turn leads to economic depression and, in its wake, global inflation.

I could go on, but I hope I’ve made the point: Parker’s book illustrates encyclopaedically how relatively small movements in the climate generated outsized economic and political consequences. These were badly handled in the 17th century, and the result was calamitous for humanity.

So to today’s weather, and today’s climate.

When ‘Climategate’ erupted at the University of East Anglia back in 2009, it left me profoundly suspicious of the intellectual firepower, data-competence and even basic honesty of those involved in warning us of climate change. In particular, there was a ‘readme.txt’ file written by proper data-scientists. This file contained the house-keeping notes of what the data-scientists found as they tried to replicate the temperature series on an updated software. The reckless data-incompetence they found hidden in the code left them (and me) gobsmacked.

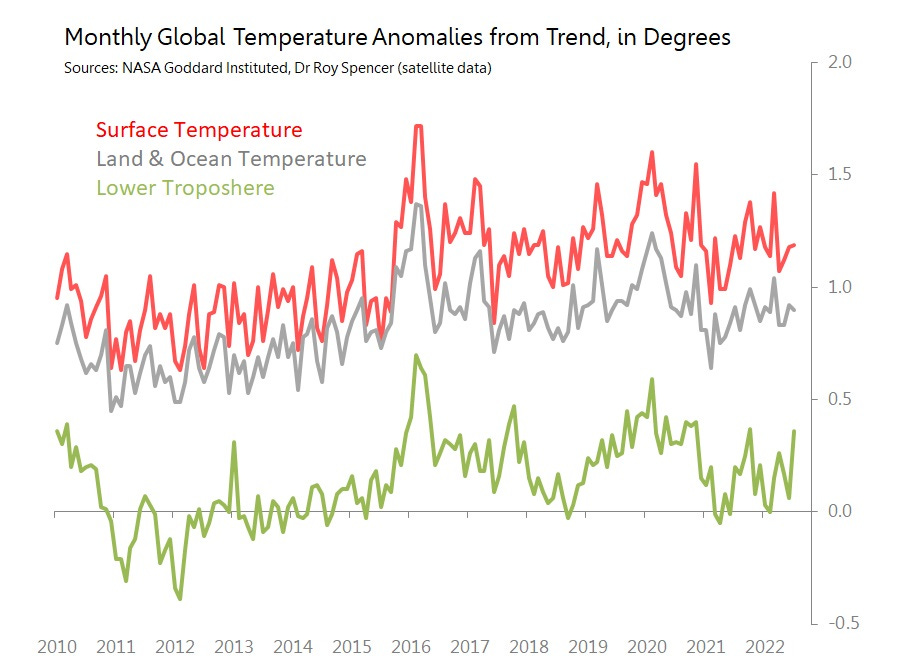

But that was back in 2009, and since then, ‘climate science’ has brought in more technically competent people, and efforts to track global temperatures are scrutinized relentlessly. Although the task of calculating/estimating a global temperature remains heroically difficult, renewed trust has been earned. Every month, I track three different global temperature records: the land and land & ocean series put out by NASA/Goddard Institute, and the satellite readings of the lower troposphere made public by Dr Roy Spencer.

Here’s what they show for this year, up to July:

What is striking about this is Jan-July 2022 has not been exceptional. You may think it has been a climatically disastrous year, but really, it has been a rather cool year by recent standards. During Jan-July, global temperatures had an average deflection against trend of 1.18 degrees, which is 0.4SDs below the 2016-2022 average for Jan-July of 1.23 degrees. Since 2016 there have only been two cooler years.

This may strike you as odd, but I do trust the data. To repeat: in terms of global temperature, 2022 has so far been moderately cool relative to recent experience.

Yet all around the Northern Hemisphere, from California to Britain to China and all points between, we are seeing extraordinary heatwaves, droughts and floods. This is a relatively mild year: if this is what happens in a mild year, what should we expect?

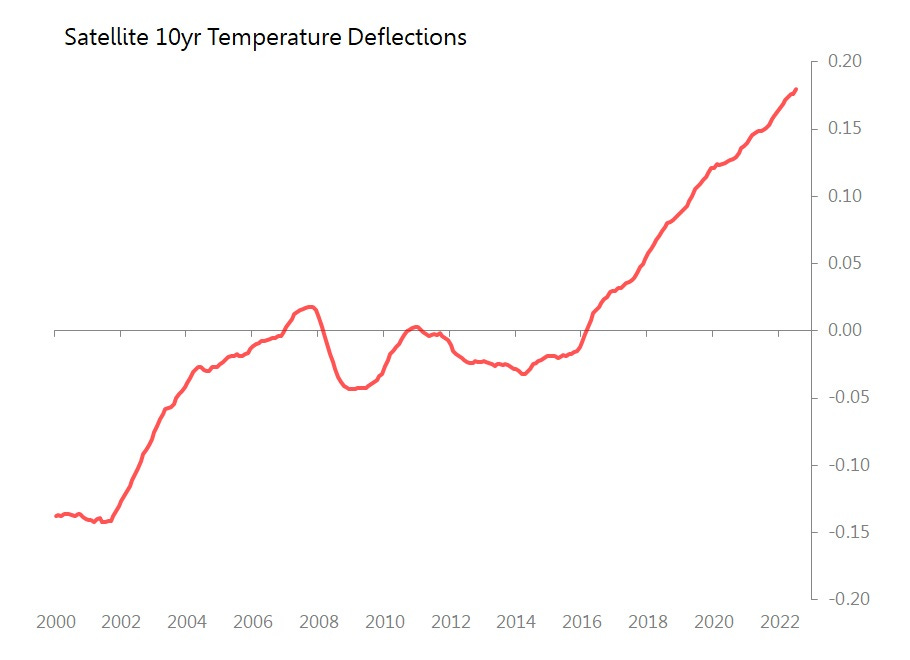

For there is no reason to doubt the underlying warming trend. Here’s a chart about how global temperatures have deflected from the l/t average since 1990.

If you don’t trust the data starting in 1990, consider the troposphere readings from satellites since 2000.

I don’t know why this is happening, and the climate system is so complicated that probably no-one else does either, really.

But as far as the UK is concerned, I’m not sure understanding matters much. If C02 concentrations are the single biggest driver, nothing the UK can do, including completely eliminating our emissions, will make the slightest difference to the global outcome. We can clutch to net zero if we want, but surely even its dedicatees must know by now this is just shaking a shamanic totem in the hope of warding off evil. It’s finding new witches, new Jews.

Quite literally, the only response which matters at this point is adaptation. That’s economic, social and - crucially - political adaptation.

If we ignore it because we don’t want to tangle with the totem-shakers, we are more likely to see mal-adaptions crawling in to occupy the policy-vacuum. We have no choice but to develop adaptational policies and adaptational politics. Do I understand what those words mean? No, not yet.

With the example of the 17th century Little Ice Age to guide us, what should be expect if we are merely entering a Little Hot Age? Perhaps getting warmer won’t be as immediately hostile to humanity as getting colder. Let’s hope. Even so, I think we can expect:

Dramatically increased volatility of weather, with increasing heatwaves, increasing drought, increasing flooding.

Larger-than-expected negative impact on global food product as marginal lands are taken out of production faster than new lands are developed.

Increased demand for fossil fuels, as the world turns up its aircon, and demands more fertilizers.

Mass population displacements, driven by drought and famine. Border incidents galore.

Above-average political volatility and a breakdown in ‘international consensus’, with rising prospects for war.

An inevitable resort to unilateral ‘geo-engineering’ efforts, which will be geo-politically destabilizing as global ‘climate’ is redistributed around the globe. The winners will call it necessary self-protection, the losers will call it war. Example: China diverts the entire Himalayan water-source. Example: geo-engineering intensifies or diminishes the monsoon. Example: the population of bone-dry Central and Western China migrates to China’s east coast, for survival.

Ever-intensifying international efforts to protect rain-forests as the remaining motors of world rainfall patterns, with ever-decreasing tolerance of national governments unwilling to take that protection seriously.

These issues are inescapably international. As such, they do not fit comfortably with a social democratic tradition which, unlike socialism or capitalism, does not have internationalism at its core. Rather, social democracy has at its core the belief in efforts to improve results at a national level. This is why the SDP backing for Brexit came naturally in a way which it never did for Labour or the Conservatives.

The most natural response for social democrats would precisely be emphasize the need for national adaptation to the New Hot Age, and be sceptical of internationally coordinated initiatives. Is that enough?

Our legacy political parties cannot be expected to think constructively, coherently, or even at all, about these issues. Yet they will be forced to confront them, probably faster than they realize. It is a challenge the SDP should not duck. As a party which seeks and expects to have to pick up the pieces eventually, we need to think hard about this now. However much we may deplore it, and fear it, if the Little Hot Age is upon us, we must prepare to find a way through the chaos.

Michael Taylor / Coldwater Economics / Coldwater Economic Substack

Michael, even with a national focus surely we can accept the signalling value of reducing contributions to the global carbon footprint and other harmful emissions. There is a significant benefit in air quality when reducing fossil fuel consumption. If smaller countries adopt the stance that they are excused from participating in the global effort to reduce emissions, especially those that have reaped most of the benefits of the increase over the last couple of centuries, then we remove incentives for larger countries to participate. Isn't effective economic policy about creating favourable incentives?

It is fascinating that the adverse geopolitical impacts you describe as a result of the global warming trend are precisely those predicted by proponents of political cycles, such as Strauss and Howe's Fourth Turning and George Friedman's institutional and socio-economic cycles. It makes me wonder if the weather played a far larger role in historical events than these commentators considered.