As I brooded over the Bank of England’s forecasts I found I was not only angry, but actually close to tears.

My angst was compounded by the Telegraph floating the idea that Jeremy ‘Strangler' Hunt plans to deepen the on-rushing recession just that little bit more by targeting capital gains tax and taxes on dividends. Because, after all, when you’re entering a depression with no obvious long-term off-ramp, what you really want to do is to beat up on savers and entrepreneurs.

All in the name of restoring financial credibility! (Btw: See below the analysis by a former President of the Reserve Bank of Minneapolis of what actually happened in the immediate aftermath of Kwasi Kwarteng’s partial budget.)

Two things make it even worse for me: first, these are policy mistakes visible from outer space, and have been from the moment the financial consequences of the pandemic hoved into view. Second, because it reminded me forcefully of a different and disastrous period of financial history I’d researched years ago: Japan 1920s.

First, Britain’s current financial problems are the result of earlier needless policy neglects. No-one likes a ‘told-you-so’ smartarse, but I’ll brave the opprobrium because its’ important to remember that today’s specific problems were predictable right from the off, and there were options to counter them. If I could spot them, how is it possible our political/economic/financial/media establishment could not? So here goes:

On May 1st 2020 I wrote ‘How to Pay for Covid-19’, published in SDPTalk, which suggested:

“The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) should be tasked to identify just how much this year’s Covid outbreak has cost the Exchequer, in terms of lost revenues and unexpected spending, unexpected debt. The OBR’s total should then be held by the [proposed 60-year] UK Covid 2020 Sinking Fund.

“By laying out an unambiguous but long-term plan to pay down that debt, the government acknowledges that fiscal responsibility has not been abandoned. It also acknowledges how the economic and financial shadow to be cast by the virus will be both broad and long – and escaping it will be, and should be, a multi-generational task. Most importantly, it divorces that question from the immediately urgent task of economic reconstruction once we’re out of lockdown.”

My worry about the lack of Treasury interest in encouraging popular investment in gilts continued. In ‘The 2021 Budget: Investment without Savings’ response to Rishi Sunak’s March 2021 budget, I wrote:

“It is simply impossible to perpetually finance the economy through pumping it full of cheap money and avoid inflation or the crowding out of productive investment spending. The concern of financing debt is especially true with the UK’s government debt, which has risen by £400 billion amid the crisis.

“There was just a dim recognition of this awkward truth, with Sunak saying that ‘while interest rates are currently forecast to remain low, there is a risk that they could rise sharply, which would have significant consequences for the affordability of debt.’ But if this is the case, then wouldn’t it surely be a good idea to encourage a stable investor base for UK government debt? The alternative is the incredibly precarious situation we have right now, where the national finances are dependent on perpetual money-printing from the Bank of England and the confidence of the banking system.

“In earlier times of massive crisis such as war, governments encouraged people to buy government bonds, such as war bonds and savings bonds. The reasons for this were a) to grow a stable investor base to moderate the volatility of interest rates, and b) to moderate the possibly volatile swings in consumption which can be expected in an immediate post-crisis environment – both these would be incredibly useful in 2021 and 2022.

“Yet there is not even a nod in this direction.”

And finally in May this year I lost my temper entirely with the whole lot of them. In ‘Wild and Dangerous: Why Britain’s Money-men Must Go’ I wrote:

“Let us remember just what the Treasury’s ‘economic strategy’ has been. At the beginning of the pandemic, the Treasury opted for a wildly unconventional set of policies: massive fiscal stimulus accompanied by massive monetary stimulus. This combination of fiscal and monetary largesse was something Britain managed to avoid even during wartime. Moreover, it was neither inevitable nor necessary: as we wrote at the time, the pandemic’s huge and extraordinary government deficit could and should have been financed by targeted public-bond sale campaigns, with the debt ring-fenced via a 60-year sinking fund. Had this strategy been pursued (or even imagined), the excesses of QE would have been avoided, and the temptation to ‘normalise’ fiscal balances immediately by tax rises would have been avoided.

“For when the pandemic retreated, in a screeching U-turn, the Treasury reversed its wildly unconventional pandemic policies to pursue a financial and economic policies so ortho-orthodox they have no followers anywhere in the world. Quite suddenly, fiscal rectitude was to be re-established by huge tax rises, even as the Bank of England tightened monetary policy. Anywhere and everywhere, if you sharply tighten fiscal policy at the same time as you are tightening monetary policy, you court recession. Which, incidentally, will leave a red imprint on your budget deficit. The fact we’ve got such dangerous drivers manically swinging the wheel this way and that is one reason why the pound is weakening. No-one wants to be a passenger in a fish-tailing taxi.”

Well, we’re all in that taxi now.

Then there’s a menacing history I’m aware of. Years ago I was managing a research outfit in Tokyo in such a lacklustre fashion I had time to investigate what on earth had happened to Japan between the end of the First World War and the early 1930s. (If you’re interested, let me know and I’ll send you the lavishly-illustrated 31 page account I wrote at the time.)

“At the end of WW1 Japan was one of the Big Powers of the world: by 1932 it was effectively isolated, its financial system was in ruins, its governing class discredited, and its state and economy menaced by the military.

“By the early 1930s even the language had exhausted the epithets of “recession” and “depression”: rather, Japanese spoke of a “national emergency” (jikyoku) and of lives “deadlocked” (yukizumari).”

Outside Tokyo, up-country, people were starving. From there it was but a short step to the invasion of Manchuria which many people now regard as the opening shots of World War 2.

The history of the concatenating errors and disasters of Japan’s 1920s are complicated and distressing. For those prepared to take my 31 pages on trust, let me pick out the bones:

Japan suffered a major terms of trade shock after the end of World War 1.

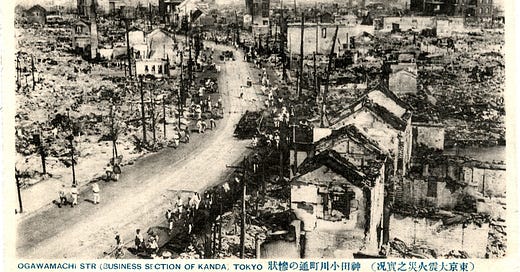

Then Japan suffered a major exogenous shock, in this case the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, which levelled Tokyo. Massive financial expansion came in response, including debt moratoria, and issuance of ‘Earthquake Bonds’ which were meant to recapitalize banks and insurance companies. Inevitably, the rescue package attracted fraud of all kinds, even as Bank of Japan’s balance sheet got loaded with bad debt.

The banking crisis hit in 1927: the result of the pre-1920 Bubble and its legacy; the financial consequences of the 1923 earthquake; the political impasse over who was to pick up the tab for the bad debts; the capture of banks by their debtors; and political skullduggery and/or error.

4. By July 1929, a new government arrived, determined that Japan’s financial credibility demanded a strict orthodoxy. “This party was traditionally the party of financial orthodoxy, and had repeatedly been willing to deflate the economy in order to inch closer to the gold standard throughout the 1920s. Finance Minister was Inoue Junnosuke – a man of great experience and with the reputation of being a safe pair of hands. A BOJ veteran, he had served as its governor for a period after 1919, had been finance minister in the Yamamoto cabinet after the great earthquake, and after the bank crisis of 1927, Finance Minister Takahashi had persuaded him to return to the governorship of the Bank of Japan for a further one-year term. If anyone had had the chance to witness Japan’s financial fragilities, it was him.

“His response to those fragilities, however, was a restatement of financial orthodoxy, combined with an energetic zeal to re-enter the gold standard at pre-war rates previously unsuspected. It fell to him to test to destruction the ideas which had gripped Japan’s establishment throughout the 1920s.”

“First he threw out budget for 1929, and recast it with radical spending cuts - even to the extent of stopping work on the current Diet building. Government spending, excluding debt service, fell 4.8% in 1929 and 11.7% in 1930. (His attempt to cut civil service, however, was aborted after ferocious resistance.) He instructed BOJ to raise interest rates. And finally, he embarked on speaking tour of the country, asserting that the economy lacked solid fundamentals, calling on public to save, to cut consumption and use domestic products.

Does all this sound familiar? History doesn’t repeat itself, but to my ears, it’s MC’ing like Eminem.

The results were, of course, disastrous for Japan with huge contractions in GDP over the next two years. In 1930 the PM was assassinated in Tokyo station, in 1931 a military coup was thwarted. By end-1931 Japan was bankrupt and the government fell. The attempt to re-establish financial credibility had bankrupted Japan, overthrown its democracy, and opened the darkest chapter in Japan’s 20th century history.

Finally, let’s remind ourselves what really happened when Kwarteng and Truss were ousted to be replaced by Sunak and Hunt. Here are the observations of Narayana Kocherlakota, professor of economics at the University of Rochester and president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis from 2009 to 2015.

“Markets didn’t oust Truss, the Bank of England did — through poor financial regulation and highly subjective crisis management.

“The big change came in the price of 30-year UK government bonds, also known as gilts, which experienced a shocking 23% drop. Most of this decline had nothing to do with rational investors revising their beliefs about the UK’s long-run prospects. Rather, it stemmed from financial regulators’ failure to limit leverage in UK pension funds. These funds had bought long-term gilts with borrowed money and entered derivative contracts to the same effect — positions that generated huge collateral demands when prices fell and yields rose. To raise the necessary cash, they had to sell more gilts, creating a doom loop in which declining prices and forced selling compounded one another.

“The Bank of England, as the entity responsible for overseeing the financial system, bears at least part of the blame for this catastrophe. As a result of its regulatory failure, it was forced into an emergency intervention, buying gilts to put a floor on prices. But it refused to extend its support beyond Oct. 14 — even though its purchases of long-term government bonds were fully indemnified by the Treasury.

“It’s hard to see how that decision aligned with the central bank’s financial-stability mandate, and easy to see how it contributed to the government’s demise.”

My guess is this one of those truths that for now is forgotten/overlooked, but which will gradually assert itself until the economic history books accept it as verifiable truth.

I have one reason only to hope. Hunt’s policies we see leaked to the press are so absurdly damaging, there remains the possibility that what we’re witnessing is a cruel head-fake, aiming to leave us all feeling relieved when the fiscal tightening less Carthaginian than currently seems likely. Let’s hope.

Michael Taylor / Coldwater Economics / Coldwater Economics Substack

Though it was the Pension Fund LDI situation that sank the markets, why didn't the Treasury and BofE not know about it ? Of course they did. But left Truss to hang herself.

Why scrap infrastructure projects in the North, but carryon in the South ?

Why scrap all the supply side aimed incentives for SMEs?

Why scrap development zones?

Increase capital gains

Increase CTax

Be anti capitalist ? In a G7 country that has just left the EU.