This piece details what I believe is the most expensive blunder in the history of British government finance. It’s a mistake which will bloat your tax bill, shrivel your services, and put Britain under a cloud of financial pressure for a generation. And it was not only avoidable, it was predictable.

The speculation that Simon ‘Hilarious’ Case may leave his position as head of the Civil Service is welcome. Mr Case’s contribution to the Hancock Whatapp files shows an unforgettable contempt for the public he is paid to serve. The fish rots from the head, so Lord alone knows what depths of contempt and disdain for us those serving under him must harbour.

But of course, when our distant establishment which enjoys its ‘sneer of cold command’ is involved, things can always get worse. And so we come to the speculation that Mr Case’s successor will be non-other than ex-Treasury supremo Sir Tom Scholar. Here he is - I have to say it - sneering.

The case against Tom Scholar is very simple, very clear. It is this: under Tom Scholar’s leadership, the Treasury engineered the worst financial blunder in British government history. The cost of the mistake? £200bn and rising, according to Bank of England estimates.

I do not exaggerate. The short-term funding of covid-debt was both predictable and utterly idiotic, as I specifically warned in March 2020 in a piece called ‘How to Pay for Covid’. I warned then that ‘How we pay for it will frame the economic and financial environment for at least a generation. It is probably the single most important economic, financial and political decision we will live to see.’

Now we are getting some idea of the size of the blunder. Or rather, the Bank of England itself is beginning to do the sum. Headline: just the losses on the financing - not the financing itself, just the losses we as taxpayers will need to find - are currently estimated to run up to a cumulative around £200bn. To be absolutely clear, that £200bn doesn’t include debt service or loan-losses - it’s just the losses on the financing.

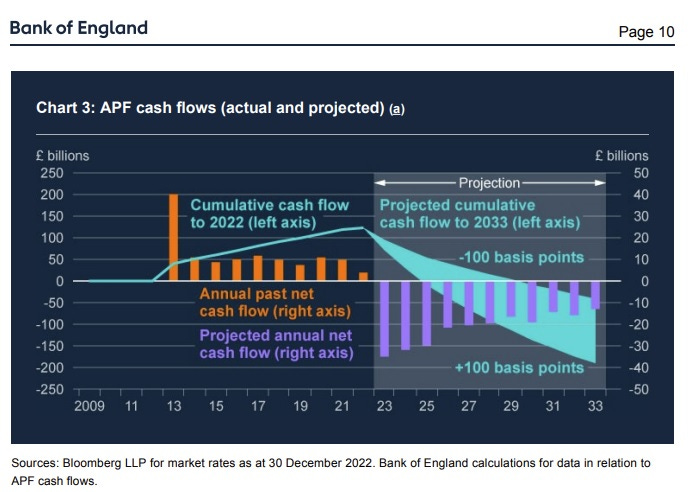

That’s Bank of England’s current estimate. You can find its estimates on page 10 of its ‘Asset Purchase Facility Quarterly Report -4Q22.’ Ultimately, as we shall see, there’s every reason to expect the bill will be higher.

£200bn in anticipated cumulative losses. How much is that? Well, it’s about 22% of last year’s government total revenues; it’s slightly more than total VAT receipts, it’s around 78% of income tax receipts, and 113% of National Insurance Contributions.

It’s just under double the interest we paid last year on government debt. It’s equivalent to around 80% of spending on social benefits.

What’s behind those losses? The logic is simple: when bonds pay a fixed interest rate, the value of holding that bond will fluctuate according to what is happening to market interest rates. If market interest rates go up, the value of holding the bond goes down.

To take an example: in March 2020, 10yr government bonds paid an average 0.44%. If you bought a government bond for £100, it would pay you 44p a year. Right now, bond yields have gone up to around 3.8%, so if you bought a government bond for £100, you’d get £3.8 in interest. So obviously, you won’t be paying £100 for the miserly March 2020 10yr bond. Rather, to make up for the lost interest, you’d want to buy it for around £67.

The difference between the £100 you paid for it, and the £67 you could expect to sell it for represents a £33 loss.

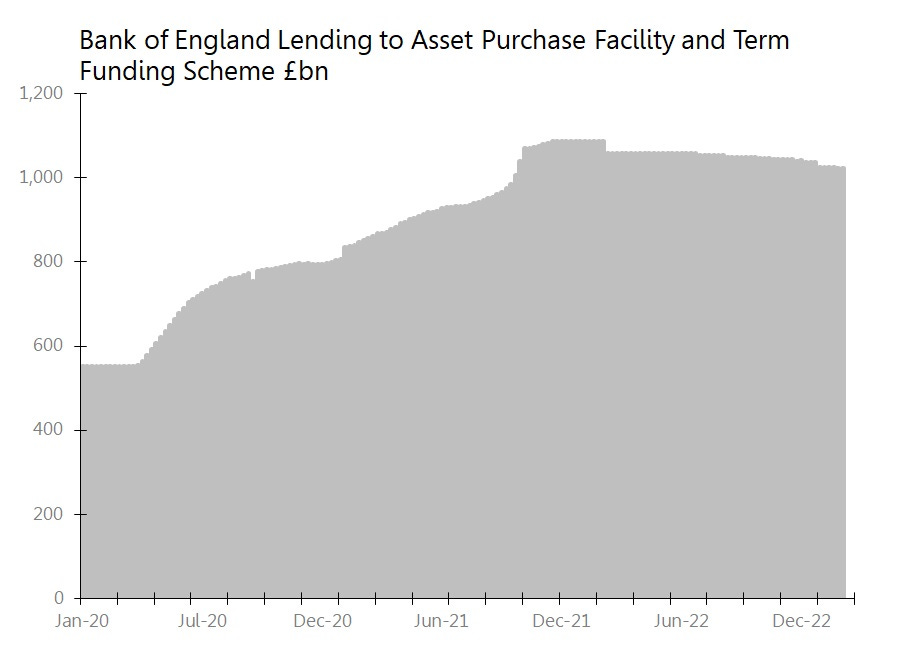

Now let’s look at how Covid-debt was financed. The heart of the financing was selling British government debt to the Asset Purchase Facility (APF), which shows up on Bank of England’s balance sheet. Between March 2020 and December 2021, the Bank’s lending to the APF rose by around £488bn to £965bn, with a further £192bn in cheap financing underwriting emergency commercial bank lending.

The crucial point is that actually what is on Bank of England’s balance sheet is not the APF itself, but rather, the loans the Bank extended to the APF, which allowed the APF to buy up the government’s covid-related debt. What you need to know is that the Treasury then indemnified the Bank of England for any losses which the APF, or the funding, or re-funding, of it, generated. That’s why you the taxpayer are on the hook.

If the APF bought the Gilt at £100 and it’s now worth only £67 because of interest rate rises, the Treasury needs to pay the Bank that £33 difference. That sounds hypothetical. It isn’t: the Bank is expecting losses of about £35bn this year, and around £30bn in 2024 and 2025 each.

Of course, whilst this is the principle at the heart of the £200bn likely loss estimate, in practice there exact size of the loss will depend on the precise maturity mix of the government debt the APF bought, the likely trajectory of short-term rates and long-term bond yields, and the cost of re-funding that position. On that basis, the BOE’s end-January estimate of around £200bn is probably already around £40bn too low, given the c 50bps rise in bond yields since then.

From here, every percentage point rise in interest rate rises, and/or bond yields looks likely to add approximately £75bn to the estimated accumulated losses. How likely are further interest rate rises? Well, we’ve got double digit inflation and bond yields of 3.8%. What do you think is going to happen?

A final thought, and one which is utterly damning. Had the government decided to finance covid-related debt properly, for example by selling long-dated bonds and putting them into a sinking fund, we could now be buying back that debt at a discount. To revert back to the bond-maths, the £33 loss could have been £33 of debt reduction through buying back the bonds cheaply.

To put it bluntly, if the blunder costs us ‘only’ £200bn, you can double that number if you include the opportunity cost of debt reduction foregone.

I suppose the only rationale to restoring Tom Scholar to a senior civil service post is that he at least ought to be responsible for clearing up the mess he made. But frankly, his talents are evidently more suited to clearing up the spill in aisle six.

It’s a good question, but actually it doesn’t seem like it’s a notional ‘mark to market’ problem. Rather, if looks like it’s a funding/refunding problem. If the Bank funded a 0.4% asset short term and now finds itself refunding that holding at 4%, the losses get booked anyway. The fact that BoE is crystallising the losses now and is doing sensitivity analysis using Bank Rate assumptions strongly suggests the refunding is how the hit gets taken. Basically, it gets you one way or the other - (same maths, essentially).

As you say, not sure of the maturity profile, but if they're holding the bonds to maturity, why does the capital loss matter in the interim? Or are the positions being actively traded and the losses are, therefore, crystallised?

Not sure of the accounting practices of the BoE or APF but financial statements, generally, wouldn't be impacted by unrealised gain/loss on a Held to Maturity bond? So why are they in this instance, unless the entire portfolio is marked to market and being actively turned over?