My accomplished nephew is job-hunting: the firm he is applying to is looking for someone with acoustic engineering skills who also has enough coding knowledge to write apps in their spare time. Pretty high-spec, no?

So will he be moving to somewhere near Cambridge. No, actually: the company he hopes to join is in . . . Rotherham.

Rotherham. If you are British, you know what that signifies.

With that in mind, and on the day President Trump has announced his blue-print for global tariffs, I’m going to write about tardigrades - Britain’s industrial tardigrades.

Tardigrades are nature’s freaks: they don’t do much but they do survive. They will survive in the vacuum of outer space, and under massive pressure, they survive at all kinds of extreme temperatures. You can bombard them with radiation, and they’ll just sit there, soaking it up. Basically, they are very very hard to kill.

They do reproduce - weirdly, and after marathons of foreplay I’d certainly view as excessive.

The industrial companies surviving in England’s northern towns are our own commercial tardigrades. Much of Britain’s northern industrial towns haven’t seen genuine prosperity for decades, and in most of these towns, the degradation of their infrastructure and decline in social capital is sadly obvious (and consecrated by Treasury Green Book policy). Those industrial companies which have survived there have known only hard times, and yet they still survive. They are commercial tardigrades.

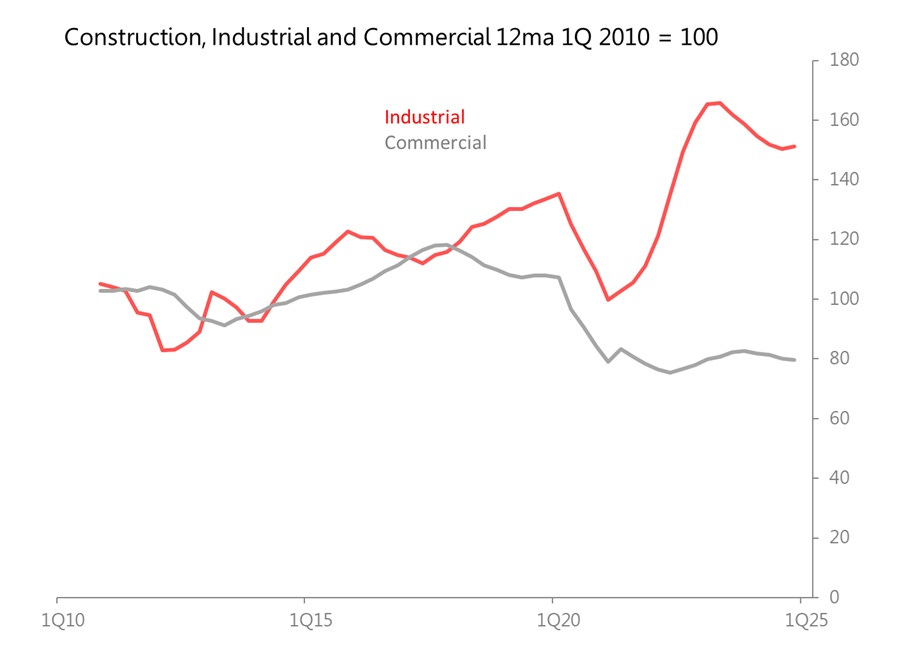

Survival is unlikely triumph. Yet it is there in the statistical evidence. Consider, for example, the way in which construction for industrial facilities has outstripped building commercial premises during the last near-decade.

Or consider the track record of manufacturing growth. Until around 2022, manufacturing output was essentially keeping pace with Britain’s services output. Britain may consider itself a service economy which has abandoned manufacturing, but the abandoned sector, like the baby in the woods, was surviving. Until around 2022.

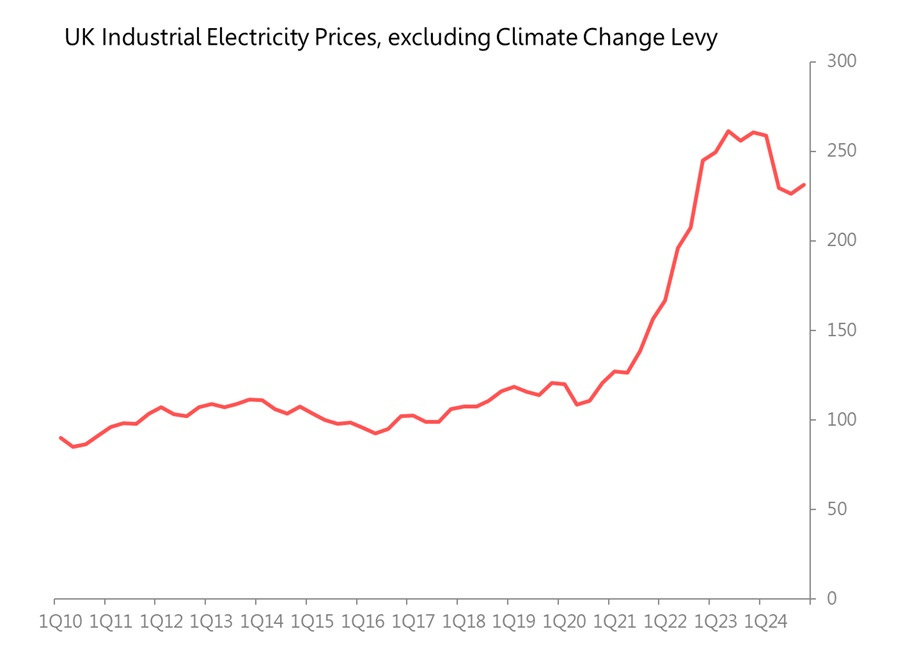

No surprises for what happened then: Britain’s industrial base got hit by a dramatic rise in electricity input prices. This was the product of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Britain’s electricity pricing policy. Electricity prices are (insanely) determined by the stand-by price commanded by Britain’s army of emergency gas turbines. These turbines can essentially charge whatever they like when they are called on to cover up for the shortcomings of the country’s sacrosanct reliance on reliably intermittent ‘renewables’. So they do, and industry winces at the bills.

If Britain’s industrial tardigrades can survive Britain’s energy policy, they can survive anything. Considering what they have gone through, a paltry 10% tariff on exports will be water off a tardigrade’s back.

Now let’s consider how manufacturing has fared relative to the overall economy in England’s regions. We can do this by looking at 20 yrs worth of data for 38 different cities/regions showing growth overall gross value added, the gross value added by manufacturing, and the gross value added of public admin. You can find the data for this (and much more) here.

For the purposes of this I am going to contrast two types of cities/regions. First, those in which i) growth in manufacturing GVA has outpaces overall GVA despite ii) growth in public sector services has been significantly below average or even absolutely. Instinctively, I consider these cities/regions to be England’s great economic survivors, and I’m going to call them the Tardigrades.

I contrast them with a second set of cities/regions, in which i) manufacturing has actually shrunk in GVA terms, but in which GVA has been partly rescued by above average GVA growth in public services. I’ll call them them Lush Places / Life Support.

Instinctively, I think that as globalization goes into retreat and stresses on public finances become difficult to ignore, England needs more of the first set, fewer of the second set.

The Tardigrades and the Lush Places

So here they are: the places where England’s industrial tardigrades can be found. At the top of the list are Greater Cambridge (soi disant) and Oxfordshire, where sharply above average gross value added output has been led by manufacturing, with little or no contribution from a rise in public sector value added. If the whole of England was like Oxford and Cambridge, England would be in a great place.

But it’s the ones at the bottom of the league table which are really eye-opening: in Lincolnshire, Hull and East Yorkshire, York and North Yorkshire and Dorset, the overall gross value added has been lower, but it has been fired lopsidedly by very sharp rises in manufacturing value added, almost always compensating for a sharp withdrawal of public services. If all of England was like this, the country’s future may not be sparkling growth, but neither would it be disastrous.

This regional database shows average GVA of public services during this period at 9.9%. For the Tardigrades, the average is minus 2.5%.

But all of England is not occupied by Industrial Tardigrades: it also has its Lush Places and Life Support where manufacturing has withered, and where the local economy has been propped up by sharply higher than average expansion of the public sector.

Most of these places have seen an absolute decline in gross value added from manufacturing during this period, most dramatically in Greater Birmingham, West of England and the Black Country. But as manufacturing has shrunk here, the local economy has been bolstered by sharp rises in public sector work.

This regional database shows average GVA of public services during this period at 9.9%. For the Tardigrades, the average is +23.2%

These are the regions which look most exposed to a deglobalizing world in which public finances are permanently stretched. How they will re-discover a commercial base having lost manufacturing infrastructures and become significantly more reliant on public sector work remains to be seen.